Vector Algebra

Vectors are mathematical objects possessing both magnitude and direction. They are fundamental in mathematics and the sciences for describing physical quantities like displacement, velocity, force, and fields. In this chapter, we will formalize the concept of vectors in two- and three-dimensional space, establishing the algebraic framework for their manipulation. This algebraic structure provides a powerful bridge to geometric intuition, allowing us to model and solve complex problems.

Definitions

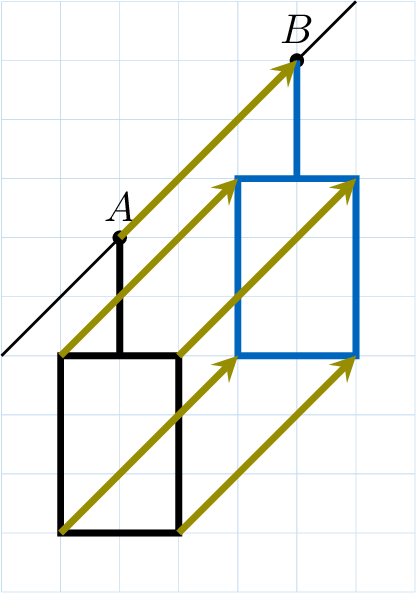

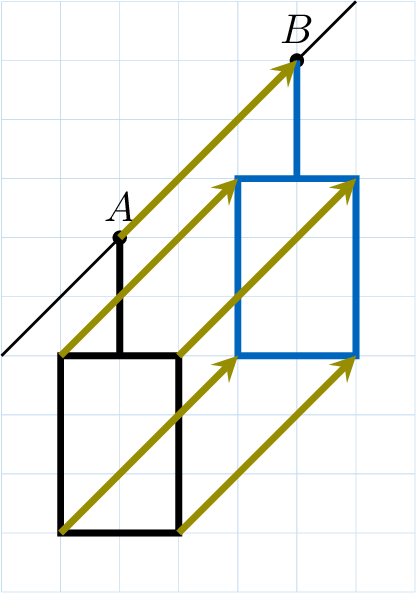

Moving a figure by translation means sliding the figure without rotating it. To describe this movement, we use an arrow \(\vec{u}\) called a vector. To translate all points by a vector, we can use:

- the length of the arrow (magnitude) and its direction (orientation and sense);

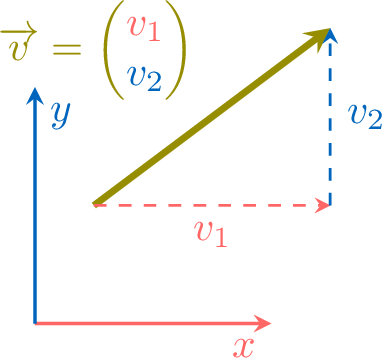

- the horizontal (or \(x\)-) and vertical (or \(y\)-) components of the vector (how many units to the right/left and up/down).

Definition Vector

A vector is defined by:

- Geometrically, as a directed line segment, characterized by a magnitude (length) and a direction (including its sense).

- Algebraically, as an ordered set of components. In a Cartesian coordinate system, a vector in 2D is \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \end{pmatrix}\) and in 3D is \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \\ v_3 \end{pmatrix}\).

Two Point Notation

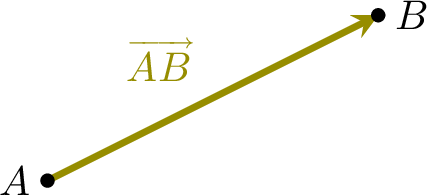

Definition Two Point Notation

The vector from a starting point \(A\) to an endpoint \(B\) is denoted by \(\Vect{AB}\).

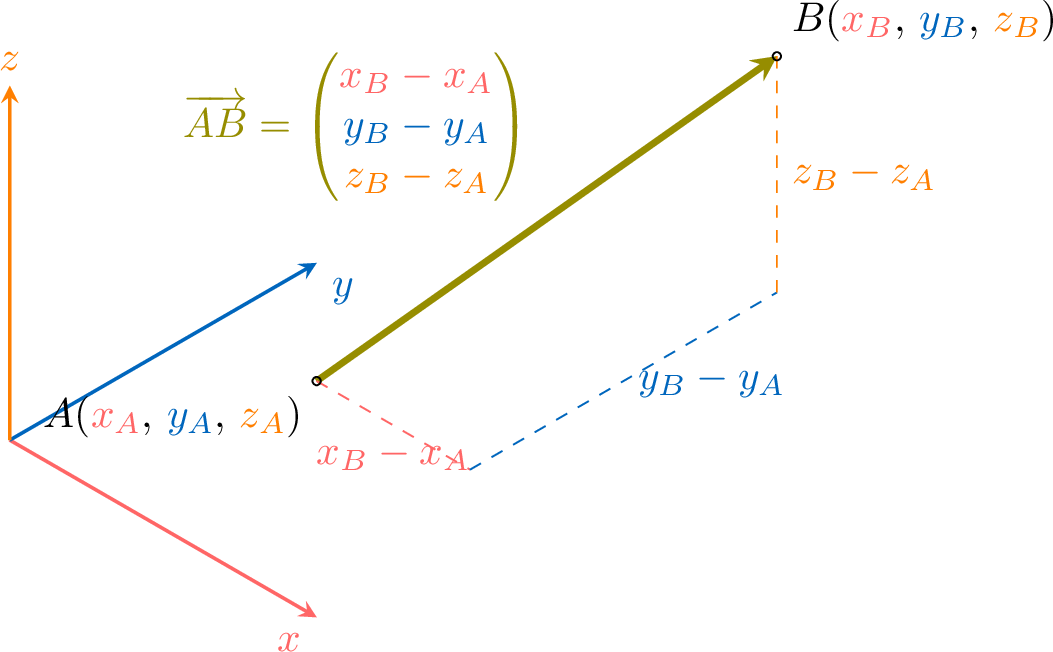

Proposition Components of \(\Vect{AB}\)

The components of the vector \(\Vect{AB}\) are found by subtracting the coordinates of the starting point from the coordinates of the endpoint.

- In 2D, for points \(A(x_A, y_A)\) and \(B(x_B, y_B)\): $$\Vect{AB} = \begin{pmatrix}x_B - x_A \\

y_B - y_A\end{pmatrix}$$

- In 3D, for points \(A(x_A, y_A, z_A)\) and \(B(x_B, y_B, z_B)\): $$\Vect{AB} = \begin{pmatrix}x_B - x_A \\

y_B - y_A \\

z_B - z_A \end{pmatrix}$$

Base Vectors

When we plot vectors in the Cartesian plane, we move first in the \(x\)-direction and then in the \(y\)-direction.

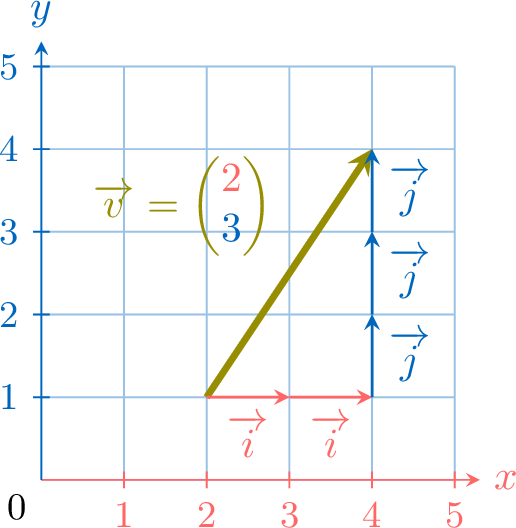

For example, to plot the vector \(\Vect{v}=\begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix}\), we move 2 units in the \(x\)-direction, and then 3 units in the \(y\)-direction.

Let \(\Vect{i}=\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) be a translation 1 unit in the positive \(x\)-direction and \(\Vect{j}=\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) be a translation 1 unit in the positive \(y\)-direction. This movement is equivalent to \(2\) times \(\Vect{i}\) plus \(3\) times \(\Vect{j}\):$$\begin{aligned}\Vect{v} & =2 \Vect{i}+3 \Vect{j} \\ \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix} & =2\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}+3\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\end{aligned}$$

For example, to plot the vector \(\Vect{v}=\begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix}\), we move 2 units in the \(x\)-direction, and then 3 units in the \(y\)-direction.

Let \(\Vect{i}=\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) be a translation 1 unit in the positive \(x\)-direction and \(\Vect{j}=\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\) be a translation 1 unit in the positive \(y\)-direction. This movement is equivalent to \(2\) times \(\Vect{i}\) plus \(3\) times \(\Vect{j}\):$$\begin{aligned}\Vect{v} & =2 \Vect{i}+3 \Vect{j} \\ \begin{pmatrix} 2 \\ 3 \end{pmatrix} & =2\begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}+3\begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\end{aligned}$$

Definition Base Vectors

The standard basis vectors are unit vectors along the coordinate axes.

- In 2D: \(\Vect{i} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\Vect{j} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\). Any vector can be written as$$\Vect{v} = \underbrace{v_1\Vect{i} + v_2\Vect{j}}_{\textcolor{colordef}{\text{unit vector form}}}=\underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \end{pmatrix}}_{\textcolor{colordef}{\text{component form}}}$$

- In 3D: \(\Vect{i} = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\), \(\Vect{j} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix}\), and \(\Vect{k} = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix}\). Any vector can be written as$$\Vect{v} = \underbrace{v_1\Vect{i} + v_2\Vect{j}+ v_3\Vect{k}}_{\textcolor{colordef}{\text{unit vector form}}}=\underbrace{\begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2\\ v_3 \\ \end{pmatrix}}_{\textcolor{colordef}{\text{component form}}}$$

Equality between Vectors

Two vectors are considered equal if they represent the exact same displacement, regardless of their starting point.

Definition Geometric Equality of Vectors

Two vectors are equal if they have:

\(\textcolor{olive}{\Vect{u}} = \textcolor{olive}{\Vect{v}}\)

- the same direction (they are parallel),

- the same sense,

- and the same magnitude (length).

\(\textcolor{olive}{\Vect{u}} = \textcolor{olive}{\Vect{v}}\)

Definition Algebraic Equality of Vectors

Two vectors are equal if their corresponding components are equal.

- In 2D: \(\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}x'\\y'\end{pmatrix} \iff x = x' \text{ and } y = y'\).

- In 3D: \(\begin{pmatrix}x\\y\\z\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}x'\\y'\\z'\end{pmatrix} \iff x = x',\; y = y', \text{ and } z = z'\).

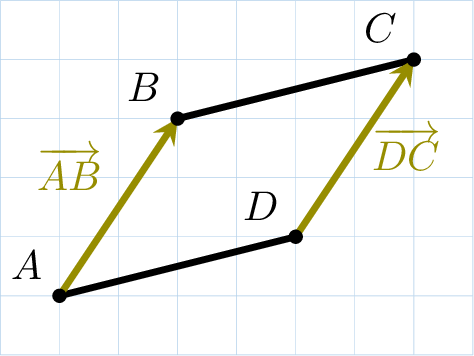

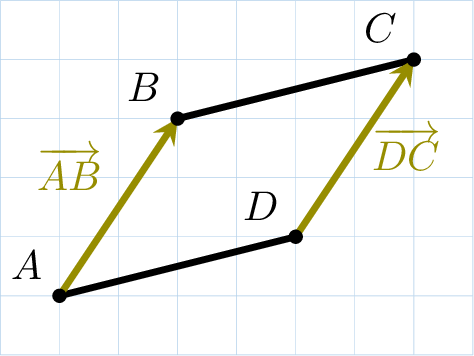

Proposition Parallelogram criterion

For four points \(A\), \(B\), \(C\), and \(D\) such that no three are collinear, the vectors \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{DC}\) are equal if and only if the quadrilateral \(ABCD\) is a parallelogram.

Vector Addition and Subtraction

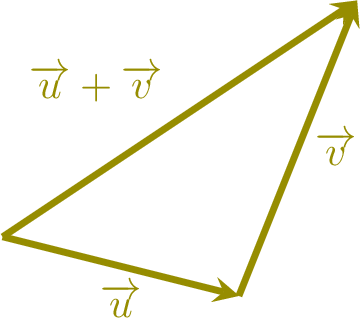

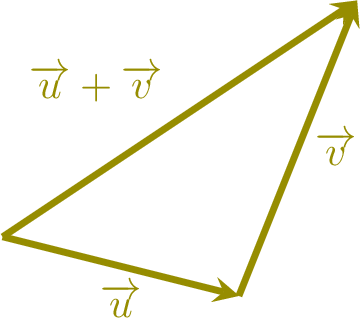

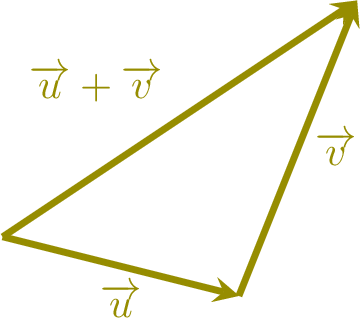

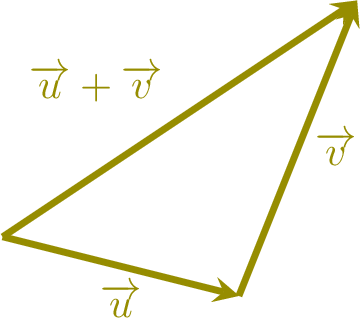

Suppose we perform a translation by vector \(\Vect{u}\) followed by a translation by vector \(\Vect{v}\). This is equivalent to a single translation by a resultant vector, which we call the sum \(\Vect{u}+\Vect{v}\).

Definition Vector Addition

The sum of two vectors is found by adding their corresponding components.

- In 2D:\(\begin{pmatrix}u_1\\ u_2\end{pmatrix}+\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}u_1+v_1\\ u_2+v_2 \end{pmatrix}\)

- In 3D:\(\begin{pmatrix}u_1\\ u_2 \\ u_3\end{pmatrix}+\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2 \\ v_3\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}u_1+v_1\\ u_2+v_2 \\ u_3+v_3 \end{pmatrix}\)

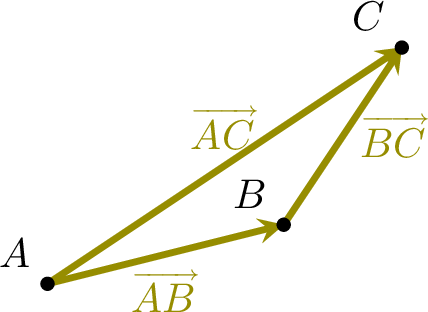

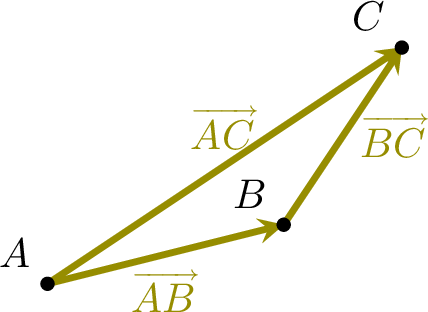

Proposition Chasles' Relation

For any three points \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\), the vector from \(A\) to \(C\) is the sum of the vector from \(A\) to \(B\) and the vector from \(B\) to \(C\):$$\Vect{AB} + \Vect{BC} = \Vect{AC}.$$

Definition Null Vector

The null vector (or zero vector), denoted \(\Vect{0}\), is the vector whose components are all zero. It is the additive identity, meaning that for any vector \(\Vect{v}\):$$ \Vect{v} + \Vect{0} = \Vect{v}. $$For any point \(A\), the vector from \(A\) to \(A\) is the null vector: \(\Vect{AA} = \Vect{0}\).

Definition Opposite Vector

For every vector \(\Vect{v}\), there exists an opposite vector, denoted \(-\Vect{v}\), such that their sum is the null vector:$$ \Vect{v} + (-\Vect{v}) = \Vect{0}. $$Geometrically, \(-\Vect{v}\) has the same magnitude and direction as \(\Vect{v}\) but the opposite sense. Algebraically, its components are the negatives of the components of \(\Vect{v}\).

- In 2D:\( -\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2 \\ \end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}-v_1\\ -v_2 \\ \end{pmatrix} \)

- In 3D:\( -\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2 \\ v_3\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}-v_1\\ -v_2 \\ -v_3 \end{pmatrix} \)

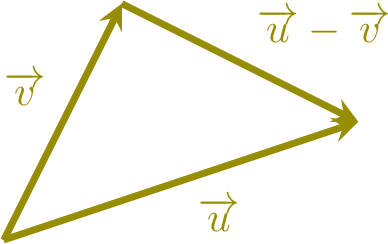

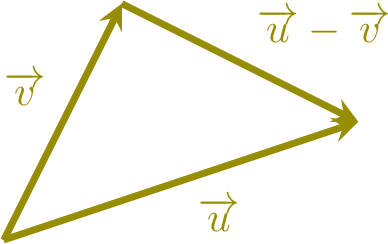

Definition Vector Subtraction

The subtraction of vector \(\Vect{v}\) from vector \(\Vect{u}\) is defined as the addition of the opposite of \(\Vect{v}\):$$\Vect{u}-\Vect{v} = \Vect{u} + (-\Vect{v}).$$The components are found by subtracting the corresponding components.

- In 2D:\(\begin{pmatrix}u_1\\ u_2\end{pmatrix}-\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}u_1-v_1\\ u_2-v_2 \end{pmatrix}\)

- In 3D:\(\begin{pmatrix}u_1\\ u_2 \\ u_3\end{pmatrix}-\begin{pmatrix}v_1\\ v_2 \\ v_3\end{pmatrix}=\begin{pmatrix}u_1-v_1\\ u_2-v_2 \\ u_3-v_3 \end{pmatrix}\)

Scalar Multiplication

Multiplying a vector by a real number (a scalar) is an operation that scales the vector. This means it changes the vector's magnitude (length) and can also reverse its sense.

Definition Scalar Multiplication

The product of a scalar \(k \in \mathbb{R}\) and a vector \(\Vect{v}\) is the vector \(k\Vect{v}\), obtained by multiplying each component of \(\Vect{v}\) by \(k\).

- In 2D:\(k\Vect{v} = k\begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} kv_1 \\ kv_2 \end{pmatrix}\)

- In 3D:\(k\Vect{v} = k\begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \\ v_3 \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} kv_1 \\ kv_2 \\ kv_3 \end{pmatrix}\)

Proposition Geometric Effect of Scalar Multiplication

Multiplying a vector \(\Vect{v}\) by a scalar \(k\) results in a new vector \(k\Vect{v}\) that is parallel to \(\Vect{v}\).

- If \(k > 0\), \(k\Vect{v}\) has the same sense as \(\Vect{v}\).

- If \(k < 0\), \(k\Vect{v}\) has the opposite sense to \(\Vect{v}\).

- If \(k = 0\), the result is the null vector: \(0\Vect{v} = \Vect{0}\).

Magnitude and Unit Vectors

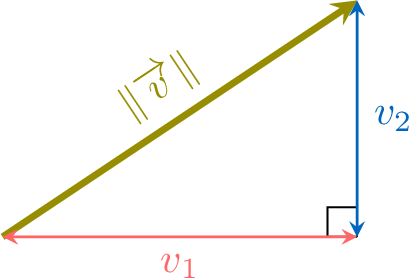

The magnitude (or norm) of a vector is its length. It is a scalar quantity, denoted \(\|\Vect{v}\|\). We can calculate it by applying the Pythagorean theorem to its components.

Definition Magnitude of a Vector

The magnitude of a vector \(\Vect{v}\) is the square root of the sum of the squares of its components.

- In 2D, for \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \end{pmatrix}\): $$ \|\Vect{v}\| = \sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2 }. $$

- In 3D, for \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} v_1 \\ v_2 \\ v_3 \end{pmatrix}\): $$ \|\Vect{v}\| = \sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2 + v_3^2}. $$

Definition Unit Vector

A unit vector is a vector \(\Vect{v}\) with a magnitude of 1, such that \(\|\Vect{v}\|=1\).

Example

The standard basis vectors \(\Vect{i}\), \(\Vect{j}\), and \(\Vect{k}\) are all unit vectors.

Method Normalisation

The process of finding a unit vector in the same direction as a given vector is called normalisation. To find the unit vector in the direction of a non-zero vector \(\Vect{v}\), we divide the vector by its own magnitude:$$\frac{\Vect{v}}{\|\Vect{v}\|}.$$

Parallel Vectors

Two vectors are considered parallel if they share the same direction. This means they lie on the same line or on parallel lines. The concept of parallel vectors is fundamental to determining if geometric objects like lines are parallel or if points are aligned on a single line.

Definition Parallel (Collinear) Vectors

Two vectors \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) are parallel (or collinear) if one is a scalar multiple of the other. That is, if there exists a real number \(k\) such that:$$\Vect{u} = k \Vect{v}.$$

Remarks

- This implies that the components of parallel vectors are proportional.

- The zero vector \(\Vect{0}\) is parallel to every vector \(\Vect{u}\), since \(\Vect{0} = 0 \cdot \Vect{u}\).

Proposition Geometric Applications

- Two lines \(\Line{AB}\) and \(\Line{CD}\) are parallel if and only if their direction vectors \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{CD}\) are parallel.

- Three points \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\) are collinear (lie on the same straight line) if and only if the vectors \(\Vect{AB}\) and \(\Vect{AC}\) are parallel.

Definition Determinant of Two Vectors

Let \(\Vect{u} = \begin{pmatrix} x \\ y \end{pmatrix}\) and \(\Vect{v} = \begin{pmatrix} x' \\ y' \end{pmatrix}\) be two vectors in the plane. The determinant of \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) is the real number:$$\det(\Vect{u},\,\Vect{v}) =\begin{vmatrix}x & x' \\

y & y'\end{vmatrix}= xy' - yx'.$$

Proposition Condition for Parallelism

Two vectors \(\Vect{u}\) and \(\Vect{v}\) in a plane are parallel if and only if their determinant is zero:$$\det(\Vect{u},\,\Vect{v}) = 0.$$

Example

Let \(A(1, 2)\), \(B(5, 4)\), \(C(-1, -1)\), and \(D(5, 2)\). Are the lines \(\Line{AB}\) and \(\Line{CD}\) parallel?

The lines are parallel if their direction vectors are parallel. Let's compute the vectors and their determinant:$$ \Vect{AB} = \begin{pmatrix}5-1 \\

4-2\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}4 \\

2\end{pmatrix}, \quad\Vect{CD} = \begin{pmatrix}5-(-1) \\

2-(-1)\end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix}6 \\

3\end{pmatrix}. $$$$ \det(\Vect{AB},\,\Vect{CD}) =\begin{vmatrix}4 & 6 \\

2 & 3\end{vmatrix}= (4)(3) - (6)(2) = 12 - 12 = 0. $$Since the determinant is zero, the vectors are parallel, and therefore the lines \(\Line{AB}\) and \(\Line{CD}\) are parallel.