Differential Calculus

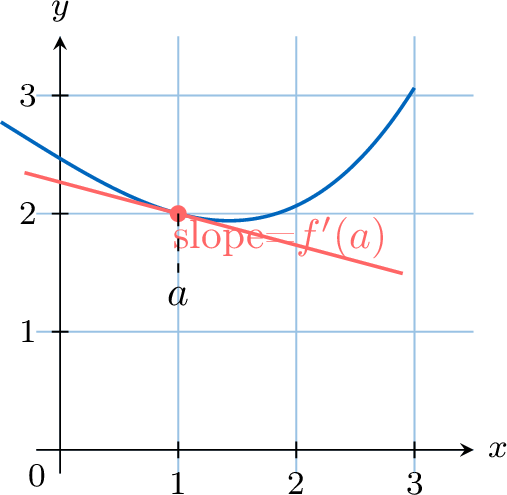

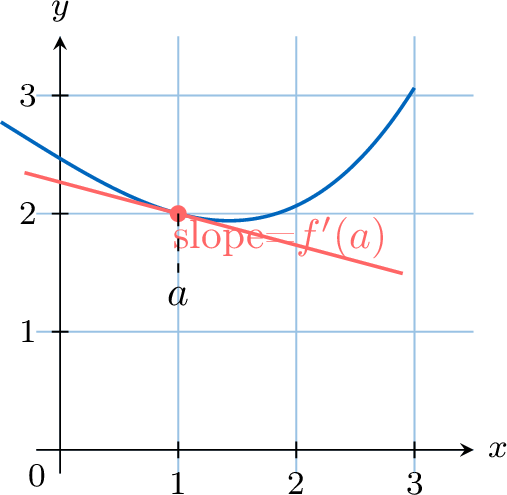

Differential calculus is a branch of mathematics that deals with rates of change. The derivative of a function at a chosen input value describes the instantaneous rate of change of the function at that value. The process of finding a derivative is called differentiation. Geometrically, the derivative at a point is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of the function at that point.

We have previously differentiated simple functions involving powers of \(x\). In this chapter, we will explore the rules and techniques for differentiating more complicated functions.

We have previously differentiated simple functions involving powers of \(x\). In this chapter, we will explore the rules and techniques for differentiating more complicated functions.

Derivative

Rate of Change

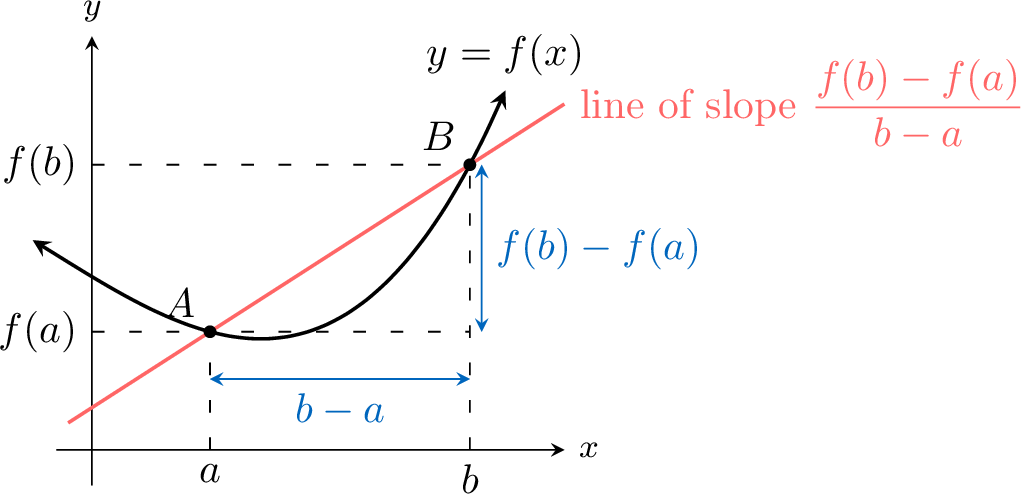

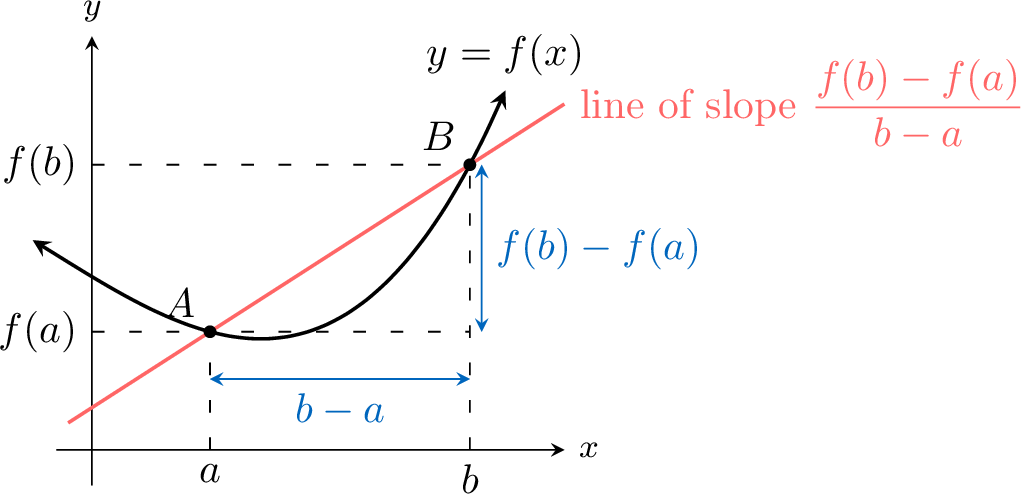

Definition Rate of Change

The rate of change of a function \(f\) between two points \(A(a, f(a))\) and \(B(b, f(b))\) is the gradient of the secant line \((AB)\).$$ \textcolor{colordef}{\text{Rate of change} = \dfrac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}} $$

Limit Definition of the Derivative

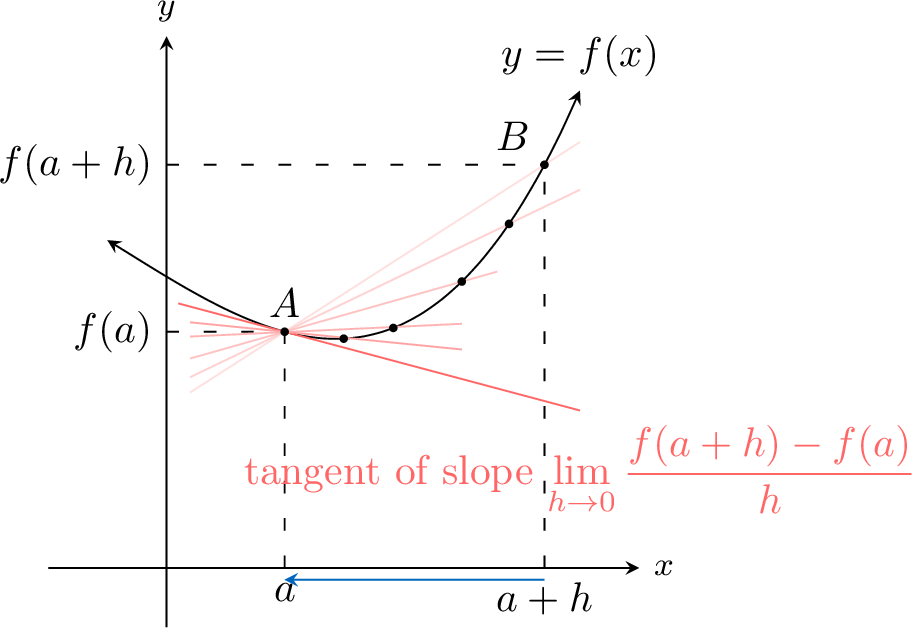

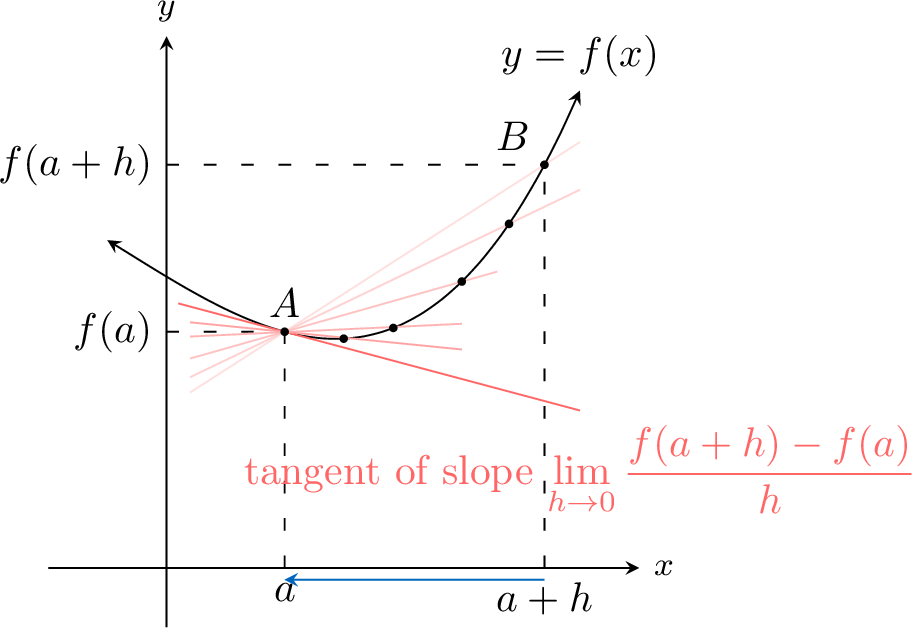

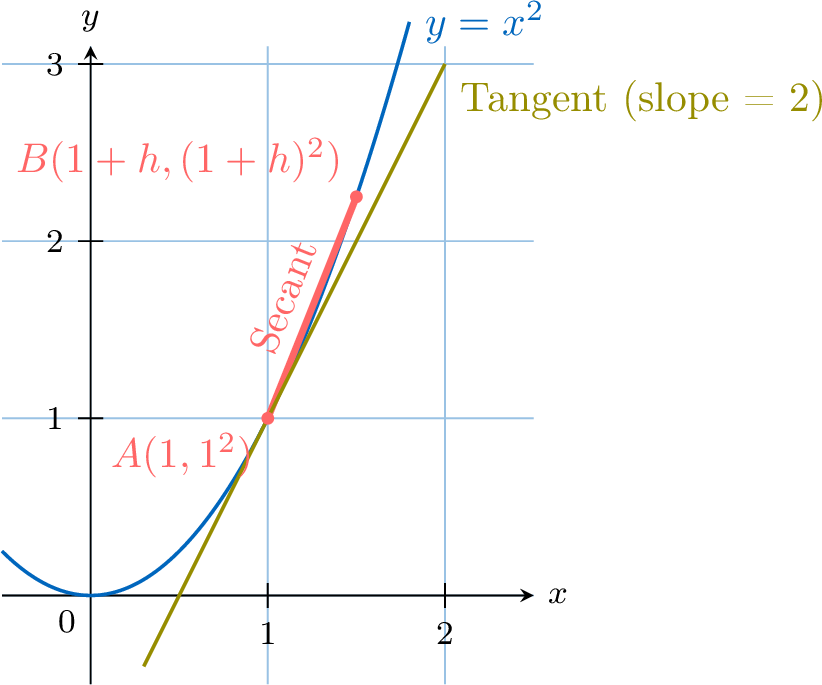

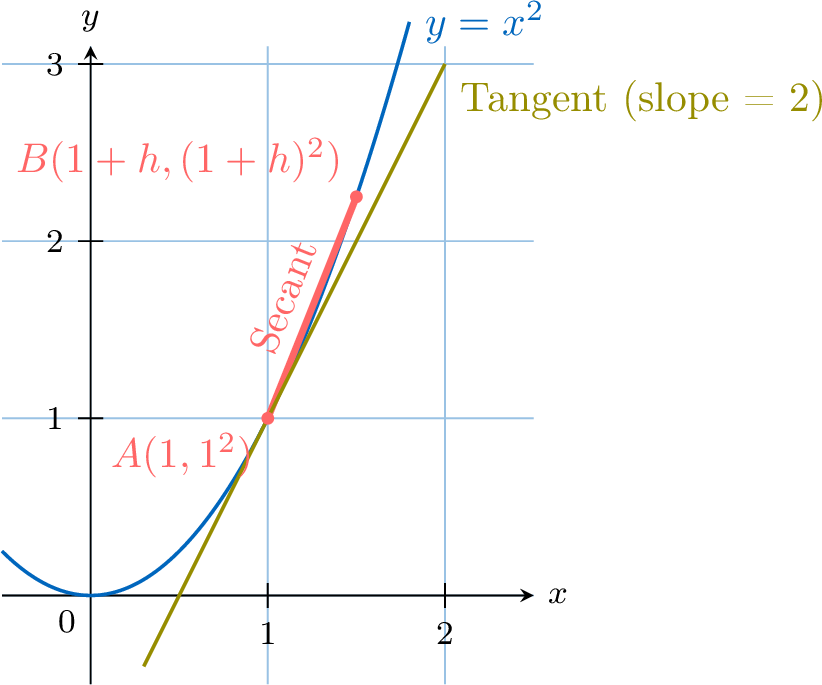

To find the rate of change at a single point \(A\), we can examine the average rate of change over a very small interval. Let the second point be \(B(a+h, f(a+h))\), where \(h\) is a small change in \(x\). The gradient of the secant line \((AB)\) is given by:$$ \dfrac{f(a+h) - f(a)}{(a+h)-a} = \dfrac{f(a+h) - f(a)}{h} $$As we let \(B\) get closer to \(A\), the value of \(h\) approaches 0. The secant line approaches the tangent line at point A. The limit of the secant slopes is the slope of the tangent, which we define as the instantaneous rate of change.

Definition The Derivative at a Point

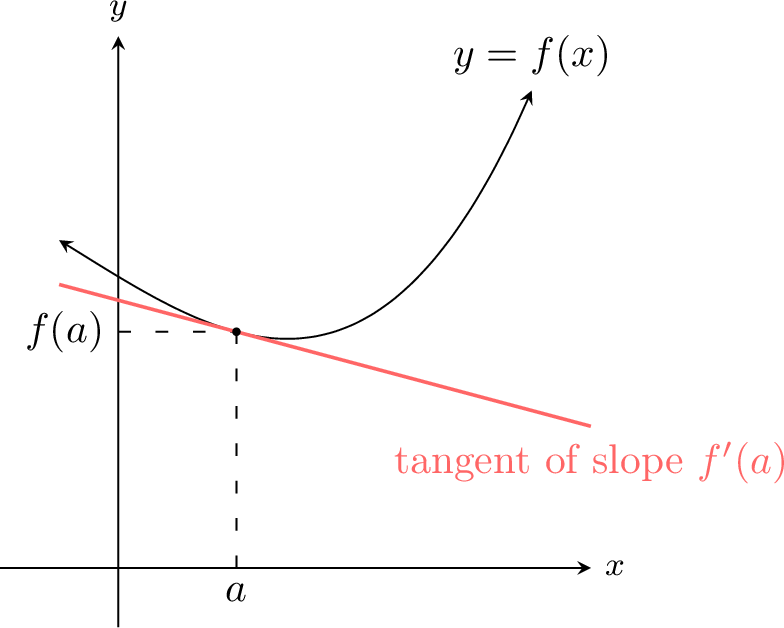

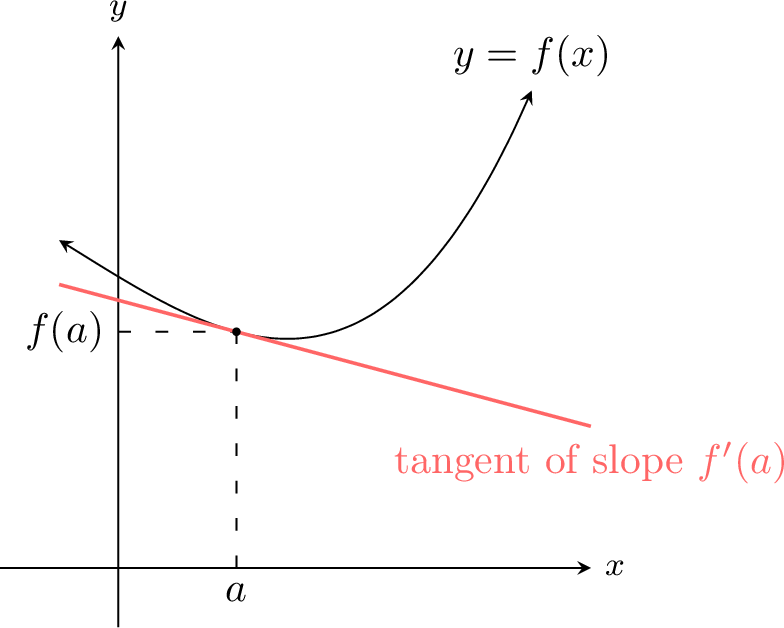

The derivative of a function \(f\) at a point \(a\), denoted \(f'(a)\), is the instantaneous rate of change of the function at that point. It is defined by the limit:$$ \textcolor{colordef}{f'(a) = \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{f(a+h)-f(a)}{h}} $$Geometrically, \(f'(a)\) is the slope of the tangent line to the graph of \(f\) at the point \((a, f(a))\).

Example

Use first principles to find the derivative of \(f(x)=x^2\) at the point \(x=1\).

We evaluate the limit of the rate of change as \(h \to 0\).$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{f(1+h)-f(1)}{h} &= \dfrac{(1+h)^2 - 1^2}{h} \\

&= \dfrac{(1+2h+h^2) - 1}{h} \\

&= \dfrac{2h+h^2}{h} \\

&= \dfrac{h(2+h)}{h} \\

&= 2+h \quad (\text{for } h \neq 0)\end{aligned}$$Now, we take the limit:$$ f'(1) = \lim_{h \to 0} (2+h) = 2 $$The derivative at \(x=1\) is 2. This means the slope of the tangent line to the graph of \(f(x)=x^2\) at the point \((1,1)\) is 2. The diagram below shows how the slope of the secant line from \((1,1)\) to \((1+h, f(1+h))\) approaches the slope of the tangent as \(h\) gets smaller.

Derivative Function

By finding the derivative at a general point \(x\) instead of a specific point \(a\), we can construct a new function, \(f'(x)\), whose value at any \(x\) is the slope of the tangent to the original function \(f(x)\) at that point.

The process of finding the derivative using this limit is called differentiation from first principles.

The process of finding the derivative using this limit is called differentiation from first principles.

Definition The Derivative Function

The derivative function of \(f\), denoted \(f'\), is the function defined by:$$ f'(x) = \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h} $$

Example

For \(f(x)=x^2\), find \(f'(x)\).

We evaluate the limit of the rate of change.$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h} &= \dfrac{(x+h)^2 - x^2}{h} \\

&= \dfrac{x^2+2xh+h^2-x^2}{h} \\

&= \dfrac{2xh+h^2}{h}\\

&= \dfrac{h(2x+h)}{h}\\

& = 2x+h \quad (\text{for } h \neq 0)\\

&\xrightarrow[h \to 0]{ } 2x.\end{aligned}$$So$$ f'(x) = \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h} = 2x $$

While the "prime" notation \(f'(x)\) is compact, an alternative notation developed by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz is often more descriptive and versatile, especially when dealing with the chain rule or differential equations.

Definition Leibniz Notation

If \(y\) is a function of \(x\), i.e., \(y=f(x)\), the derivative function can be written as:$$ \textcolor{colordef}{\dfrac{dy}{dx}} $$This is read as "dee y by dee x" and represents the derivative of \(y\) with respect to the variable \(x\).

- The term \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\) should be thought of as a single operator, not a fraction. However, it is derived from the idea of the fraction \(\dfrac{\Delta y}{\Delta x}\) as the change in \(x\) becomes infinitesimally small.

- We can also use the notation \(\dfrac{d}{dx}[f(x)]\), which is read as "the derivative with respect to \(x\) of \(f(x)\)".

Example

For \(y=x^2\), find \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\).

The derivative of \(x^2\) is \(2x\). In Leibniz notation, we write:$$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} = 2x $$

Conditions of Differentiability

Before we explore more advanced differentiation rules, it is important to understand the conditions under which a function can be differentiated. This brings us to the concepts of continuity and differentiability.

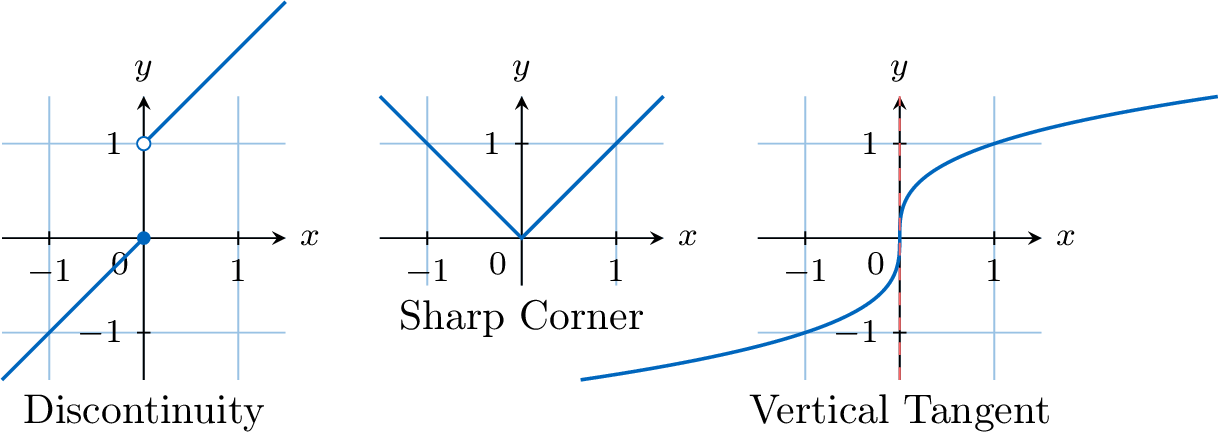

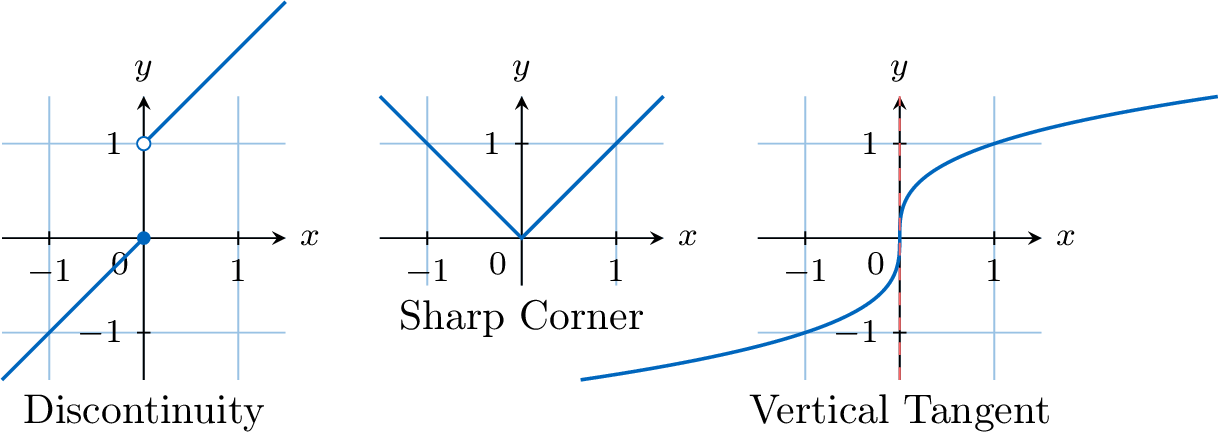

- A function is continuous if its graph can be drawn without lifting your pen from the paper. There are no breaks, holes, or jumps.

- A function is differentiable if it is continuous and its graph is "smooth," meaning it has no sharp corners or vertical tangents.

Proposition When a Function is Not Differentiable

A function \(f\) is not differentiable at a point \(x=a\) if its graph has:

- A discontinuity (a hole or jump).

- A sharp corner (where the slope from the left does not equal the slope from the right).

- A vertical tangent (where the slope is infinite).

Example

The graph of a function \(y=f(x)\) is shown. At which x-values is the function not differentiable, and why?

The function is not differentiable at two points:

- At \(\boldsymbol{x=-1}\), there is a jump discontinuity. Since the function is not continuous here, it cannot be differentiable.

- At \(\boldsymbol{x=1}\), there is a sharp corner. The slope of the line segment from the left is \(-0.5\), while the tangent to the parabola from the right has a slope of \(-2(1-2)=2\). Since the left and right slopes are not equal, the function is not differentiable at this point.

Rules of Differentiation

While finding a derivative from first principles using the limit definition is fundamental to understanding the concept, it is often a long and repetitive process. To differentiate more complex functions efficiently, mathematicians have developed a set of powerful rules. This section will introduce these essential rules, which form the bedrock of practical differentiation. By mastering them, you will be able to find the derivative of almost any function you encounter.

Basic Rules and Power Functions

We begin with the foundational rules that apply to the most common components of functions, such as constants, powers, and simple arithmetic combinations. These rules can be used to differentiate any polynomial function, as well as many other simple functions, without having to use the limit definition each time.

Proposition Basic Derivative Rules

- Constant Rule: If \(f(x)=c\), then \(f'(x)=0\).

- Power Rule: If \(f(x)=x^n\), then \(f'(x)=nx^{n-1}\) for any \(n \in \mathbb{R}\).

- Constant Multiple Rule: If \(f(x)=c \cdot u(x)\), then \(f'(x)=c \cdot u'(x)\).

- Sum Rule: If \(f(x)=u(x) + v(x)\), then \(f'(x)=u'(x) + v'(x)\).

Proof for if \(f(x)=u(x)+v(x)\), then \(f'(x)=u'(x)+v'(x)\):

We evaluate the limit of the rate of change.$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h} &= \dfrac{\left[u(x+h)+v(x+h)\right] - \left[u(x)+v(x)\right]}{h} \\ &= \dfrac{\left[u(x+h)-u(x)\right] + \left[v(x+h)-v(x)\right]}{h} \\ &= \dfrac{u(x+h)-u(x)}{h} + \dfrac{v(x+h)-v(x)}{h} \\ &\xrightarrow[h \to 0]{ } u'(x) + v'(x)\quad \text{(sum of limits)}.\end{aligned}$$So \( f'(x) = u'(x)+v'(x) \).

The other proofs are done in Examples.

We evaluate the limit of the rate of change.$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{f(x+h)-f(x)}{h} &= \dfrac{\left[u(x+h)+v(x+h)\right] - \left[u(x)+v(x)\right]}{h} \\ &= \dfrac{\left[u(x+h)-u(x)\right] + \left[v(x+h)-v(x)\right]}{h} \\ &= \dfrac{u(x+h)-u(x)}{h} + \dfrac{v(x+h)-v(x)}{h} \\ &\xrightarrow[h \to 0]{ } u'(x) + v'(x)\quad \text{(sum of limits)}.\end{aligned}$$So \( f'(x) = u'(x)+v'(x) \).

The other proofs are done in Examples.

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = 4x^3 - 5x^2 + 7x - 2\).

We apply the rules to each term:$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= \dfrac{d}{dx}(4x^3) - \dfrac{d}{dx}(5x^2) + \dfrac{d}{dx}(7x) - \dfrac{d}{dx}(2) \\

&= 4(3x^2) - 5(2x) + 7(1) - 0 \\

&= 12x^2 - 10x + 7\end{aligned}$$

Chain Rule

Many complex functions are created by composing simpler ones. A composite function has the form \(f(x) = v(u(x))\), where one function (the "inner" function, \(u\)) is the input to another (the "outer" function, \(v\)). For example, in the function \(f(x) = (x^2+1)^3\), the inner function is \(u(x)=x^2+1\) and the outer function is \(v(x)=x^3\).

The Chain Rule provides a powerful method for differentiating such functions by finding the derivatives of the inner and outer functions separately.

The Chain Rule provides a powerful method for differentiating such functions by finding the derivatives of the inner and outer functions separately.

Proposition Chain Rule

If \(f(x)=v(u(x))\) then:$$ f'(x) = v'(u(x)) \cdot u'(x) $$In Leibniz notation, if \(y=v(u)\) then$$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} = \dfrac{dy}{du} \cdot \dfrac{du}{dx} $$

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = (x^2+1)^3\).

- Using prime notation:

Let the outer function be \(v(x)=x^3\) and the inner function be \(u(x)=x^2+1\). We have \(f(x)=v(u(x))\). The derivatives are \(v'(x)=3x^2\) and \(u'(x)=2x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= v'(u(x)) \cdot u'(x) \\ &= 3(u(x))^2 \cdot (2x) \\ &= 3(x^2+1)^2 \cdot (2x)\\ &= 6x(x^2+1)^2\end{aligned}$$ - Using Leibniz's notation (\(y=f(x)\)):

For \(y=u^3\) and \(u=x^2+1\), the derivatives are \(\frac{dy}{du}=3u^2\) and \(\frac{du}{dx}=2x\).$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{dy}{dx} &= \dfrac{dy}{du} \cdot \dfrac{du}{dx} \\ &= (3u^2) \cdot (2x) \\ &= 3(x^2+1)^2 \cdot (2x)\\ & = 6x(x^2+1)^2\end{aligned}$$

Product Rule

While the derivative of a sum is the sum of the derivatives, the same is not true for a product. To find the derivative of a function that is the product of two other functions, such as \(f(x) = x^2 \sin(x)\), we must use a specific formula called the Product Rule.

Proposition Product Rule

If \(f(x)=u(x)v(x)\), then$$ f'(x) = u'(x)v(x) + u(x)v'(x) $$In Leibniz notation, if \(y=u\cdot v\) :$$ \dfrac{dy}{dx}= \dfrac{du}{dx}v + u\dfrac{dv}{dx} $$

In words: "The derivative of the first times the second, plus the first times the derivative of the second."

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = (x+1)(x^2+3)\).

- Using prime notation:

For \(f(x)=u(x)v(x)\) where \(u(x)=x+1\) and \(v(x)=x^2+3\), the derivatives are \(u'(x)=1\) and \(v'(x)=2x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= u'(x)v(x) + u(x)v'(x) \\ &= (1)(x^2+3) + (x+1)(2x) \\ &= x^2+3 + 2x^2+2x \\ &= 3x^2+2x+3\end{aligned}$$ - Using Leibniz's notation (\(y=f(x)\)):

For \(y=uv\) where \(u=x+1\) and \(v=x^2+3\), the derivatives are \(\frac{du}{dx}=1\) and \(\frac{dv}{dx}=2x\).$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{dy}{dx} &= \dfrac{du}{dx}v + u\dfrac{dv}{dx} \\ &= (1)(x^2+3) + (x+1)(2x) \\ &= x^2+3 + 2x^2+2x \\ &= 3x^2+2x+3\end{aligned}$$

Quotient Rule

Just as with products, finding the derivative of a quotient of two functions requires a specific formula. The Quotient Rule is used to differentiate functions of the form \(f(x) = \dfrac{u(x)}{v(x)}\), such as \(f(x) = \dfrac{e^x}{x^2+1}\).

Proposition Quotient Rule

For \(f(x)=\dfrac{u(x)}{v(x)}\), then$$ f'(x) = \dfrac{u'(x)v(x) - u(x)v'(x)}{[v(x)]^2} $$In Leibniz notation, \(y=\dfrac{u}{v}\), then$$ \frac{dy}{dx} = \dfrac{\frac{du}{dx}v - u\frac{dv}{dx}}{v^2} $$

We can write the quotient as a product:$$ f(x) = \frac{u(x)}{v(x)} = u(x) \cdot [v(x)]^{-1} $$Let \(a(x) = u(x)\) and \(b(x) = [v(x)]^{-1}\). The derivatives are:

- \(a'(x) = u'(x)\)

- Using the chain rule for \(b(x)\), we get \(b'(x) = -1 \cdot [v(x)]^{-2} \cdot v'(x) = -\dfrac{v'(x)}{[v(x)]^2}\).

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = \frac{x}{x+1}\).

- Using prime notation:

For \(f(x)=\frac{u(x)}{v(x)}\) where \(u(x)=x\) and \(v(x)=x+1\), the derivatives are \(u'(x)=1\) and \(v'(x)=1\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= \frac{u'(x)v(x) - u(x)v'(x)}{[v(x)]^2} \\ &= \frac{(1)(x+1) - (x)(1)}{(x+1)^2} \\ &= \frac{x+1-x}{(x+1)^2} \\ &= \frac{1}{(x+1)^2}\end{aligned}$$ - Using Leibniz's notation \((y=f(x))\):

For \(y=\frac{u}{v}\) where \(u=x\) and \(v=x+1\), the derivatives are \(\frac{du}{dx}=1\) and \(\frac{dv}{dx}=1\).$$\begin{aligned}\frac{dy}{dx} &= \frac{\frac{du}{dx}v - u\frac{dv}{dx}}{v^2} \\ &= \frac{(1)(x+1) - (x)(1)}{(x+1)^2} \\ &= \frac{x+1-x}{(x+1)^2} \\ &= \frac{1}{(x+1)^2}\end{aligned}$$

Implicit Differentiation

So far, we have differentiated functions that were defined explicitly, in the form \(y=f(x)\). However, some curves are defined implicitly by a relation between \(x\) and \(y\), such as the circle \(x^2+y^2=25\). In these cases, it may be difficult or impossible to solve for \(y\) directly. Implicit differentiation allows us to find \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\) without solving for \(y\).

Method Implicit Differentiation Procedure

- Differentiate both sides of the equation with respect to \(x\).

- When differentiating a term involving \(y\), apply the chain rule. Since \(y\) is a function of \(x\), the derivative of \(y\) is \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\). For example, \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(y^3) = 3y^2 \cdot \dfrac{dy}{dx}\).

- After differentiating, solve the resulting equation for \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\).

Example

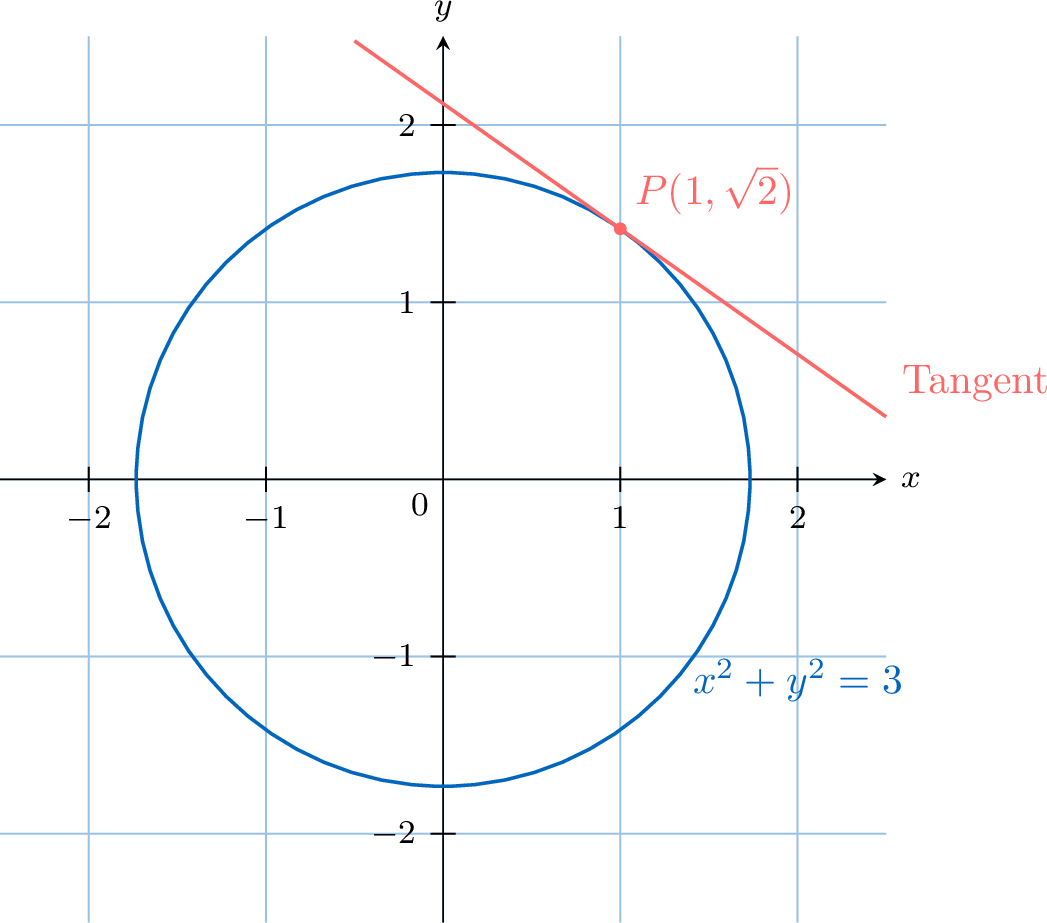

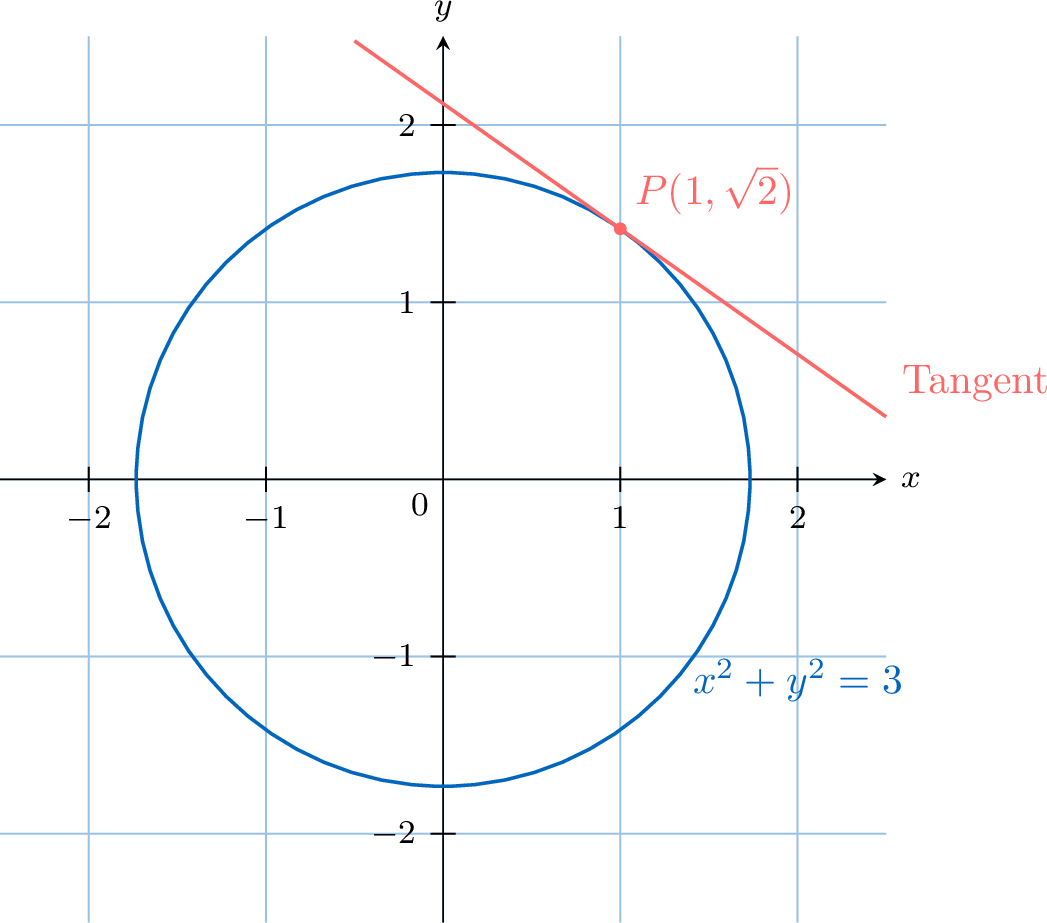

Find \(\dfrac{dy}{dx}\) for the circle \(x^2+y^2=3\).

Differentiate both sides with respect to \(x\):$$\begin{aligned} \dfrac{d}{dx}(x^2+y^2)& = \dfrac{d}{dx}(3) \\

\dfrac{d}{dx}(x^2) + \dfrac{d}{dx}(y^2)& = 0 \quad (\text{linearity})\\

2x + 2y \cdot \dfrac{dy}{dx} &= 0 \quad (\text{chain rule})\\

2y\dfrac{dy}{dx} &= -2x \\

\dfrac{dy}{dx}&= -\dfrac{x}{y} \quad (\text{for }y\neq 0)\\

\end{aligned} $$The slope of the tangent at any point \((x,y)\) on the circle is given by \(-x/y\).

For example, at the point \(P(1, \sqrt{2})\) on the circle, the slope of the tangent is \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = -\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\).

For example, at the point \(P(1, \sqrt{2})\) on the circle, the slope of the tangent is \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = -\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\).

Derivatives of Standard Functions

Having established the fundamental rules for combining derivatives (Sum, Product, Quotient, and Chain Rules), we now turn to finding the derivatives of the most important families of functions: exponential, logarithmic, and trigonometric functions.

These functions form the building blocks of most mathematical models in science and engineering. Memorizing their derivatives, along with the rules for combining them, will give you the complete toolkit needed to differentiate nearly any function encountered in this course. Each of these derivatives can be proven from the limit definition, but they are used so frequently that they should be committed to memory.

These functions form the building blocks of most mathematical models in science and engineering. Memorizing their derivatives, along with the rules for combining them, will give you the complete toolkit needed to differentiate nearly any function encountered in this course. Each of these derivatives can be proven from the limit definition, but they are used so frequently that they should be committed to memory.

Exponential Functions

The exponential function, particularly \(f(x)=e^x\), holds a unique and fundamental place in calculus. Its rate of change is directly proportional to its value, which makes it the mathematical language of many natural processes like population growth and compound interest. We will see that this function has a remarkably simple derivative.

Proposition Derivative of \(e^x\)

The derivative of the natural exponential function is itself:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(e^x) = e^x $$

Using the limit definition of the derivative:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(e^x) = \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{e^{x+h} - e^x}{h} = \lim_{h \to 0} \dfrac{e^x e^h - e^x}{h} = \lim_{h \to 0} e^x \left(\dfrac{e^h - 1}{h}\right) $$Since \(e^x\) does not depend on \(h\), we can move it outside the limit:$$ = e^x \cdot \lim_{h \to 0} \left(\dfrac{e^h - 1}{h}\right) $$The limit \(\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{e^h-1}{h}\) is a fundamental limit which is equal to 1.

Therefore, \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(e^x) = e^x \cdot 1 = e^x\).

Therefore, \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(e^x) = e^x \cdot 1 = e^x\).

Proposition Chain Rule for \(e^{u(x)}\)

The derivative of an exponential function with a function in the exponent is given by:$$ \left(e^{u(x)}\right)' = e^{u(x)}u'(x) $$In Leibniz notation:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}\left(e^{u}\right) = e^{u}\dfrac{du}{dx} $$

Let the outer function be \(v(u) = e^u\) and the inner function be \(u(x)\).

Then, \(e^{u(x)} = v(u(x))\).

Then, \(e^{u(x)} = v(u(x))\).

- The derivative of the outer function \(v(u) = e^u\) with respect to \(u\) is \(v'(u) = e^u\).

- The derivative of the inner function \(u(x)\) with respect to \(x\) is \(u'(x)\).

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x)=e^{x^2}\).

Here, the inner function is \(u(x)=x^2\), so \(u'(x)=2x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= e^{u(x)}u'(x)\\

&= e^{x^2}2x\end{aligned} $$

Proposition Derivative of \(a^x\)

For any base \(a>0\), the derivative of \(f(x)=a^x\) is:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(a^x) = \ln(a) \cdot a^x $$

$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{d}{dx}(a^x) &= \dfrac{d}{dx}(e^{x\ln(a)})&(a^x = e^{\ln\left(a^x\right)} = e^{x\ln(a)})\\

&= e^{x\ln(a)}\dfrac{d}{dx}\left(x\ln(a)\right) \\

&= a^x\cdot \ln(a) \\

\end{aligned}$$

Logarithmic Functions

The natural logarithm function, \(f(x)=\ln(x)\), is the inverse of the exponential function \(e^x\). This inverse relationship is the key to finding its derivative. Just as the exponential function has a remarkably simple derivative, so does the logarithm. This derivative is fundamental in calculus, particularly in integration, as it allows us to find the antiderivative of functions of the form \(1/x\).

Proposition Derivative of \(\ln x\)

The derivative of the natural logarithm function for \(x>0\) is:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\ln x) = \dfrac{1}{x} $$

Let \(y = \ln x\). By the definition of the natural logarithm, this means \(e^y = x\). We can now differentiate this implicit equation with respect to \(x\), using the chain rule on the left side:$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{d}{dx}(e^y) &= \dfrac{d}{dx}(x) \\

e^y \cdot \dfrac{dy}{dx} &= 1 \\

\dfrac{dy}{dx} &= \dfrac{1}{e^y}\end{aligned}$$Since we know that \(e^y = x\), we substitute this back into the expression:$$ \dfrac{dy}{dx} = \dfrac{1}{x} $$

Proposition Chain Rule for \(\ln(u(x))\)

The derivative of the natural logarithm of a function is given by:$$ \left(\ln(u(x))\right)' = \dfrac{u'(x)}{u(x)} $$In Leibniz notation:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\ln(u)\right) = \dfrac{1}{u}\,\dfrac{du}{dx} $$

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = \ln(2x+3)\).

This is of the form \(\ln(u(x))\) where the inner function is \(u(x)=2x+3\).

The derivative of the inner function is \(u'(x)=2\).

Using the chain rule for logarithms:$$ f'(x) = \dfrac{u'(x)}{u(x)} = \dfrac{2}{2x+3} $$

The derivative of the inner function is \(u'(x)=2\).

Using the chain rule for logarithms:$$ f'(x) = \dfrac{u'(x)}{u(x)} = \dfrac{2}{2x+3} $$

Method Simplify Before Differentiating

For complex logarithmic functions, always use the laws of logarithms to expand or simplify the expression before differentiating. This can turn a difficult problem into a very simple one.

Recall the laws: \(\ln(ab)=\ln(a)+\ln(b)\), \(\ln(a/b)=\ln(a)-\ln(b)\), and \(\ln(a^n)=n\ln(a)\).

Recall the laws: \(\ln(ab)=\ln(a)+\ln(b)\), \(\ln(a/b)=\ln(a)-\ln(b)\), and \(\ln(a^n)=n\ln(a)\).

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = \ln\left(\dfrac{x+1}{x}\right)\).

First, we simplify the expression using the quotient rule for logarithms:$$ f(x) = \ln(x+1) - \ln(x) $$Now, we can differentiate this much simpler expression term by term:$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= \dfrac{d}{dx}(\ln(x+1)) - \dfrac{d}{dx}(\ln x) \\

&= \dfrac{1}{x+1} - \dfrac{1}{x}\end{aligned}$$

Proposition Derivative of \(\log_a(x)\)

For any base \(a>0, a\neq 1\), the derivative of \(f(x)=\log_a(x)\) is:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\log_a x) = \dfrac{1}{x\ln(a)} $$

We use the change of base formula to express the function in terms of the natural logarithm, and then differentiate.$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{d}{dx}(\log_a x) &= \dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{\ln x}{\ln a}\right) & (\text{change of base formula}) \\

&= \dfrac{1}{\ln a} \cdot \dfrac{d}{dx}(\ln x) & (\text{since } \ln a \text{ is a constant}) \\

&= \dfrac{1}{\ln a} \cdot \dfrac{1}{x} \\

&= \dfrac{1}{x\ln a}\end{aligned}$$

Trigonometric Functions

Trigonometric functions describe periodic phenomena, which are common in physics and engineering. Their derivatives follow a cyclical pattern that is both elegant and powerful. The proofs for the derivatives of \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\) are derived from the limit definition and rely on two fundamental trigonometric limits.

Proposition Fundamental Trigonometric Limits

For \(x\) in radians:$$ \lim_{x \to 0} \dfrac{\sin(x)}{x} = 1 \quad \text{and} \quad \lim_{x \to 0} \dfrac{\cos(x)-1}{x} = 0 $$

Proposition Derivatives of Sine and Cosine

The derivatives of the basic trigonometric functions are:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin x) = \cos x \quad \text{and} \quad \dfrac{d}{dx}(\cos x) = -\sin x $$

Proof for \(f(x) = \sin(x)\) using first principles and the sum-to-product identity \(\sin(A)-\sin(B) = 2\cos(\frac{A+B}{2})\sin(\frac{A-B}{2})\):$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{\sin(x+h)-\sin(x)}{h} &= \dfrac{2\cos(\frac{x+h+x}{2})\sin(\frac{x+h-x}{2})}{h} \\

&= \dfrac{2\cos(x+h/2)\sin(h/2)}{h} \\

&= \cos(x+h/2) \cdot \dfrac{\sin(h/2)}{h/2} \\

&\xrightarrow[h \to 0]{} \cos(x) \cdot 1 = \cos(x)\end{aligned}$$The proof for \(\cos(x)\) is similar.

Proposition Derivative of Tangent

The derivative of the tangent function is:$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\tan x) = 1+\tan^2 x $$

We use the quotient rule on \(f(x) = \tan x = \dfrac{\sin x}{\cos x}\).

Let \(u=\sin x\) and \(v=\cos x\). Then \(u'=\cos x\) and \(v'=-\sin x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= \dfrac{u'v - uv'}{v^2}\\ &= \dfrac{(\cos x)(\cos x) - (\sin x)(-\sin x)}{(\cos x)^2} \\ &= \dfrac{\cos^2 x + \sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x}\\ &= \dfrac{\cos^2 x}{\cos^2 x} + \dfrac{\sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x} \\ &= 1+ \dfrac{\sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x}\\ &= 1+\tan^2 x \\ \end{aligned}$$

Let \(u=\sin x\) and \(v=\cos x\). Then \(u'=\cos x\) and \(v'=-\sin x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= \dfrac{u'v - uv'}{v^2}\\ &= \dfrac{(\cos x)(\cos x) - (\sin x)(-\sin x)}{(\cos x)^2} \\ &= \dfrac{\cos^2 x + \sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x}\\ &= \dfrac{\cos^2 x}{\cos^2 x} + \dfrac{\sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x} \\ &= 1+ \dfrac{\sin^2 x}{\cos^2 x}\\ &= 1+\tan^2 x \\ \end{aligned}$$

Proposition Chain Rule for Trigonometric Functions

- \((\sin(u(x)))' = u'(x)\cos(u(x))\)

- \((\cos(u(x)))' = -u'(x)\sin(u(x))\)

- \((\tan(u(x)))' = u'(x)\bigl(1+\tan^2(u(x))\bigr)\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin(u)) = \cos(u)\dfrac{du}{dx}\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\cos(u)) = -\sin(u)\dfrac{du}{dx}\)

- \(\dfrac{d}{dx}(\tan(u)) = \bigl(1+\tan^2(u)\bigr)\dfrac{du}{dx}\)

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = \cos(x^2+3x)\).

This is of the form \(\cos(u(x))\) where the inner function is \(u(x)=x^2+3x\).

The derivative of the inner function is \(u'(x)=2x+3\).

Using the chain rule for cosine:$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= -u'(x)\sin(u(x)) \\ &= -(2x+3)\sin(x^2+3x)\end{aligned}$$

The derivative of the inner function is \(u'(x)=2x+3\).

Using the chain rule for cosine:$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= -u'(x)\sin(u(x)) \\ &= -(2x+3)\sin(x^2+3x)\end{aligned}$$

The derivatives of the remaining trigonometric functions—secant, cosecant, and cotangent—can be found by expressing them in terms of sine and cosine and then applying the Quotient Rule.

Proposition Derivatives of sec\(\virgule\) csc\(\virgule\) cot

$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\sec x) = \sec x \tan x $$$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\csc x) = -\csc x \cot x $$$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\cot x) = -\csc^2 x $$

Proof for \(f(x) = \sec x\):We write \(f(x) = \dfrac{1}{\cos x}\) and use the quotient rule with \(u=1\) and \(v=\cos x\). Then \(u'=0\) and \(v'=-\sin x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= \dfrac{u'v - uv'}{v^2} = \dfrac{(0)(\cos x) - (1)(-\sin x)}{(\cos x)^2} \\

&= \dfrac{\sin x}{\cos^2 x} = \dfrac{1}{\cos x} \cdot \dfrac{\sin x}{\cos x} \\

&= \sec x \tan x\end{aligned}$$The proofs for \(\csc x\) and \(\cot x\) are similar.

Inverse Trigonometric Functions

The inverse trigonometric functions (\(\arcsin\), \(\arccos\), \(\arctan\)) are essential in problems involving angles. Their derivatives are algebraic functions and are found using implicit differentiation.

Proposition Derivatives of Inverse Trig Functions

$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\arcsin x) = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}} $$$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\arccos x) = -\dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}} $$$$ \dfrac{d}{dx}(\arctan x) = \dfrac{1}{1+x^2} $$

Proof for \(y = \arcsin x\):If \(y = \arcsin x\), then \(\sin y = x\). We differentiate implicitly with respect to \(x\):$$\begin{aligned}\dfrac{d}{dx}(\sin y) &= \dfrac{d}{dx}(x) \\

\cos y \cdot \dfrac{dy}{dx} &= 1 \\

\dfrac{dy}{dx} &= \dfrac{1}{\cos y}\end{aligned}$$Using the identity \(\cos^2 y + \sin^2 y = 1\), we get \(\cos y = \sqrt{1-\sin^2 y}\). Since \(\sin y = x\), we have \(\cos y = \sqrt{1-x^2}\).

Substituting this back gives \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\).

Substituting this back gives \(\dfrac{dy}{dx} = \dfrac{1}{\sqrt{1-x^2}}\).

Example

Find the derivative of \(f(x) = \arctan(e^x)\).

We use the chain rule. The outer function is \(v(u) = \arctan(u)\) and the inner function is \(u(x)=e^x\).

The derivatives are \(v'(u) = \dfrac{1}{1+u^2}\) and \(u'(x)=e^x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= v'(u(x)) \cdot u'(x) \\ &= \dfrac{1}{1+(e^x)^2} \cdot e^x \\ &= \dfrac{e^x}{1+e^{2x}}\end{aligned}$$

The derivatives are \(v'(u) = \dfrac{1}{1+u^2}\) and \(u'(x)=e^x\).$$\begin{aligned}f'(x) &= v'(u(x)) \cdot u'(x) \\ &= \dfrac{1}{1+(e^x)^2} \cdot e^x \\ &= \dfrac{e^x}{1+e^{2x}}\end{aligned}$$

Second Derivative

Definition

Definition Second Derivative

The second derivative of \(f\), denoted \(f''\), is the derivative of the first derivative, \(f'\).$$ f''(x) = \dfrac{d}{dx}(f'(x)) \quad \text{ or in Leibniz notation, } \quad \dfrac{d^2f}{dx^2}= \dfrac{d}{dx}\left(\dfrac{df}{dx} \right) $$

Example

Find the second derivative of \(f(x)=x^4 - 5x^2\).

First, we find the first derivative:$$ f'(x) = 4x^3 - 10x $$Now, we differentiate again to find the second derivative:$$ f''(x) = \dfrac{d}{dx}(4x^3 - 10x) = 12x^2 - 10 $$

Finding Limits of Indeterminate Forms

L'Hôpital's Rule

When evaluating limits, direct substitution is the easiest method. However, this method sometimes results in an indeterminate form, such as \(\dfrac{0}{0}\) or \(\dfrac{\infty}{\infty}\). These forms do not have a defined value, but the limit might still exist.

For example, \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to 0} \dfrac{e^x-1}{x}\) gives \(\dfrac{0}{0}\). L'Hôpital's Rule provides a powerful technique to solve limits of these specific indeterminate forms by using derivatives.

For example, \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to 0} \dfrac{e^x-1}{x}\) gives \(\dfrac{0}{0}\). L'Hôpital's Rule provides a powerful technique to solve limits of these specific indeterminate forms by using derivatives.

Proposition L'Hôpital's Rule

Suppose \(f\) and \(g\) are differentiable functions and \(g'(x)\neq 0\) on an open interval \(I\) containing \(a\) (except possibly at \(a\) itself).

- Indeterminate Form \(\dfrac{0}{0}\):

If \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = 0\), \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = 0\) and \(\lim_{x \to a} \dfrac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}\) exists, then $$ \lim_{x \to a} \dfrac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to a} \dfrac{f'(x)}{g'(x)} $$ - Indeterminate Form \(\dfrac{\infty}{\infty}\):

If \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to a} f(x) = \pm\infty\), \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to a} g(x) = \pm\infty\) and \(\lim_{x \to a} \dfrac{f'(x)}{g'(x)}\) exists, then $$ \lim_{x \to a} \dfrac{f(x)}{g(x)} = \lim_{x \to a} \dfrac{f'(x)}{g'(x)} $$

Example

Evaluate the limit \(\displaystyle\lim_{x \to 0} \dfrac{e^{x}-1}{x}\).

First, we check the form of the limit by direct substitution:$$ \lim_{x \to 0}(e^{x}-1) = e^0-1=0 \quad \text{and} \quad \lim_{x \to 0}(x) = 0 $$This is the indeterminate form \(\dfrac{0}{0}\), so we can consider using L'Hôpital's Rule. We now find the limit of the ratio of the derivatives.$$\begin{aligned} \dfrac{\frac{d}{dx}(e^x-1)}{\frac{d}{dx}(x)} &= \dfrac{e^x}{1} \\

&\xrightarrow[x \to 0]{} \dfrac{e^0}{1} = 1\end{aligned}$$Since the limit of the derivatives exists and is equal to 1, by L'Hôpital's Rule we can conclude:$$ \lim_{x \to 0} \dfrac{e^{x}-1}{x} = 1 $$